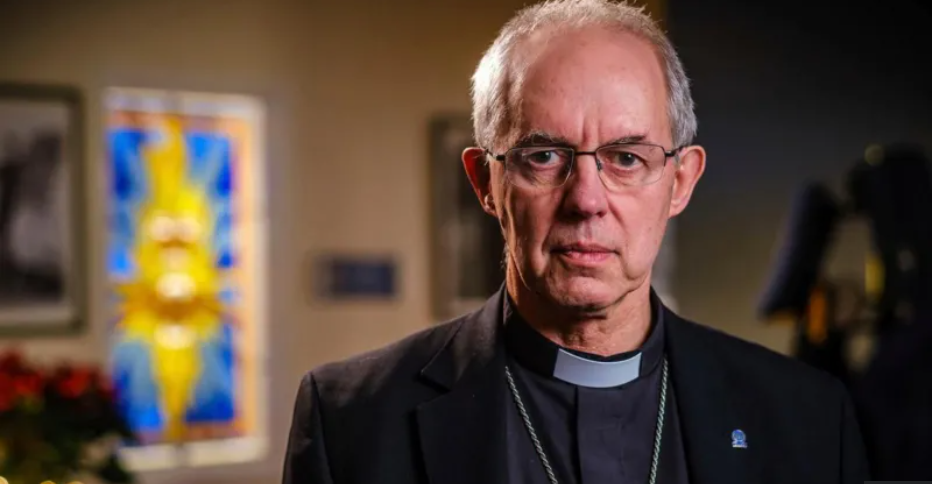

Bishop calls on Welby to resign over Church abuse scandal

A Church of England bishop has called for the resignation of the Archbishop of Canterbury, describing his position as “untenable” following a devastating report on a prolific child abuser linked to the Church.

Archbishop Welby is under increasing pressure to step down after it was revealed that he failed to rigorously follow up on reports of “abhorrent” abuse by John Smyth QC, who abused more than 100 boys and young men. A review into the Church’s handling of Smyth’s case stated that the archbishop “could and should” have reported the abuse to authorities when it was first brought to his attention in 2013.

Bishop Helen-Ann Hartley of Newcastle is the highest-ranking member of the Church to call for Justin Welby’s resignation. Others have accused the Archbishop of allowing the abuse to continue between 2013 and Smyth’s death in 2018. In an interview with the BBC on Monday, Hartley said: “Rightly, people are asking, ‘Can we trust the Church of England to keep us safe?’ And I think the answer right now is ‘no’.”

While acknowledging that Welby’s resignation would not solve the safeguarding issue, Bishop Hartley said it would be “a very clear indication that a line has been drawn” and that the Church must move toward independent safeguarding.

Welby admitted last week that the review showed he had “personally failed” by not thoroughly investigating the case and revealed that he had considered resigning but ultimately chose to remain in his position.

The Makin review concluded that Smyth could have faced justice decades earlier if the Church had reported him to the police in 2013. Three members of the General Synod, the Church’s parliament, have accused the archbishop of allowing the abuse to continue for five years. They have launched a petition for his resignation, which has garnered over 7,000 signatures.

Smyth is believed to be the Church of England’s most prolific serial abuser, having inflicted physical, sexual, psychological, and spiritual trauma on up to 130 victims.

His abuse took place over almost five decades and across three countries, according to the report. He targeted boys who attended summer camps he ran for young Christians.

Smyth abused 26 to 30 boys and young men in the UK in the 1970s and 1980s, the report found. He then relocated to Africa, where he abused a further 85 to 100 “young male children aged 13 to 17”.

The report says that from July 2013, the Church of England knew “at the highest level” about Smyth’s abuse in the UK and should have “properly and effectively” reported him to the UK police and the relevant authorities in South Africa.

Inaction from the Church represented a “missed opportunity to bring him to justice,” the report says.

Hampshire Police opened an investigation into Smyth after a Channel 4 documentary brought allegations against him to light in 2017.

Shortly after it aired, Mr Welby told Channel 4: “I genuinely had no idea that there was anything as horrific as this going on and the kind of story you showed on the clip.

“If I’d known that, I would have been very active, but I had no suspicions at all.”

But last week’s report said, “enough was known to have raised concerns upon being informed in 2013”.

Smyth died aged 75 while under investigation by Hampshire Police.

Andy Morse, one of Smyth’s victims, told the Telegraph: “I don’t believe he was telling the truth.

“I’m not sure that he would have known the detail, but I think he would have known the summary.”

The broadcaster Reverend Richard Coles said on X: “Anyone in authority who knew about an abuser and did not act properly so that abuse continued should resign.”

Anglican priest Giles Fraser told the BBC Mr. Welby had “lost the confidence of his clergy”.

Mr. Fraser, the vicar of St Anne’s Church at Kew, west London, told BBC Radio 4’s Today program Mr. Welby “really [had] to go”.

Recalling his own experience of abuse at school, Mr. Fraser said such an experience was “very traumatic and stays with you”.

“This happened to me when I was seven, eight – I’m 60 in a few weeks,” he said.

“The idea that people continued to be abused after the Church knew what was happening is disgraceful.”

Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer declined to comment when asked if Mr Welby should stand down, saying: “That’s a matter really for the Church rather than for me.”

Smyth was accused of attacking boys at his home in Winchester in the 1970s and 1980s, identifying them at Christian camps he ran and at leading public schools including Winchester College.

Smyth took them to his home where he carried out lashings with a garden cane in his shed.

One of Smyth’s victims, Bishop of Guildford Andrew Watson, previously described the “excruciating and shocking” abuse he experienced.

A report detailing Smyth’s abuse was presented to some Church leaders in 1982, but no report was made to the police.

He was encouraged to leave the country and moved to Zimbabwe and later to South Africa.

Smyth was charged with the manslaughter of a 16-year-old boy at one of his summer camps but not convicted of the offence.

In a statement, Mr Welby said he was “deeply sorry that this abuse happened” and “that concealment by many people who were fully aware of the abuse over many years meant that John Smyth was able to abuse overseas and died before he ever faced justice”.

He added: “I had no idea or suspicion of this abuse before 2013.”

What has most upset some about Church leaders’ response to the Makin review is that they feel it fits a long-running pattern of choosing a path of protecting reputation, and each other, over the welfare of abuse survivors.

In fact, the Bishop of Newcastle felt compelled to speak out after having earlier in the month received a letter from both the Archbishops of Canterbury and York over a stance that she had taken on safeguarding, using what she “experienced as coercive language”.

It relates to her imposing a ban on Archbishop of York John Sentamu preaching in her diocese, which is where he now lives, after Lord Sentamu rejected the findings of another abuse review which criticised his handling of a case where a priest abused a 16-year-old boy.

In the 1 November letter seen by the BBC, which Bishop Helen-Ann says came out of the blue, both archbishops say: “To be candid, we would very much like to see a resolution to this situation which enables Sentamu to return to ministry.”

She talks of being unsettled by the letter and by the apparent focus on Lord Sentamu and not on the abuse victim.

Reverend Matthew Ineson, a survivor of abuse by another cleric, told the BBC he believed Mr Welby should resign “and he should take with him all those who have failed in safeguarding”.

“If he doesn’t the Church is showing… again it doesn’t understand what it’s like to be a victim,” he said.

At the weekend, the Church’s lead safeguarding bishop said she welcomed Mr Welby’s apology but would not say whether he should resign.

Andrew Graystone, the author of a book about the Smyth case, said on X that he was “nervous” about calls for Mr Welby’s resignation.

“What is needed is not a scalp but a wholesale change of culture in the church,” he said.

A spokesperson for Mr Welby said the archbishop hoped the Makin review would support the ongoing work of building a safer Church, and reiterated his “horror at the scale of John Smyth’s egregious abuse, as reflected in his public apology”.

A spokesperson for the Archbishop of York said he was “saddened that this letter is now being described as coercive. This was not his intention, nor did he wish to cause any distress to the Bishop of Newcastle”.